Before

When I applied to the class, I was eager to explore how countries, specifically in their urban areas, are planning for climate change.

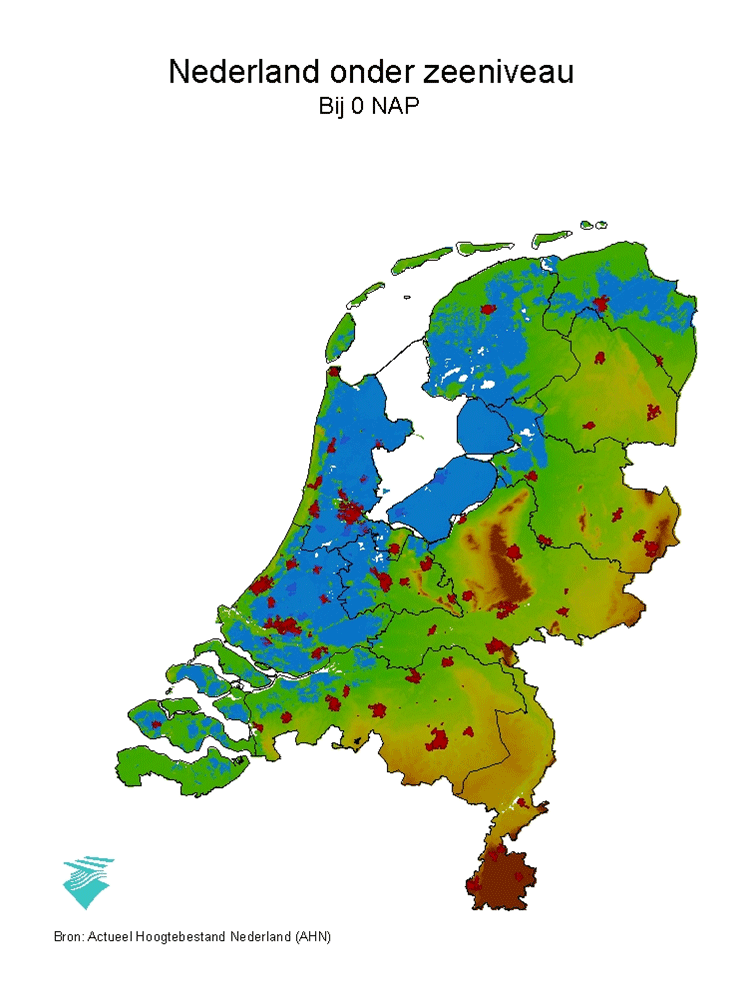

I had visited Amsterdam before. I learned from my Yellow Bike Tour guide that roughly 65% of the Netherlands would be underwater at high tide without the present system of dikes, dams, and pumps—a precarious reality amid rising sea levels due to climate change. I was captivated by the city’s architecture and the romantic canals. I longed to return to the city. This class presented the opportunity to do so through a different lens.

With a professional goal to help shape more sustainable and resilient urban environments, I saw this course an opportunity to study adaptation in a place where it’s not just a present and future concern, but embedded in their history.

Our professor, Dr. Simon Richter, came to the Dutch Water Conversation not from environmental science, but through a background in German and Dutch literature. His current research explores cultural responses to the climate emergency through projects like Poldergeist—a video animation initiative that bridges climate science and public engagement.

Professor Poldergeist, the alter ego of Professor Simon Richter

In the nine weeks before the trip, the seminar explored the historical and cultural foundations of Dutch water management. We also examined recent efforts that promote climate adaptation strategies and greater stewardship of the water and land. With this knowledge, we prepared to engage with experts in the Netherlands.

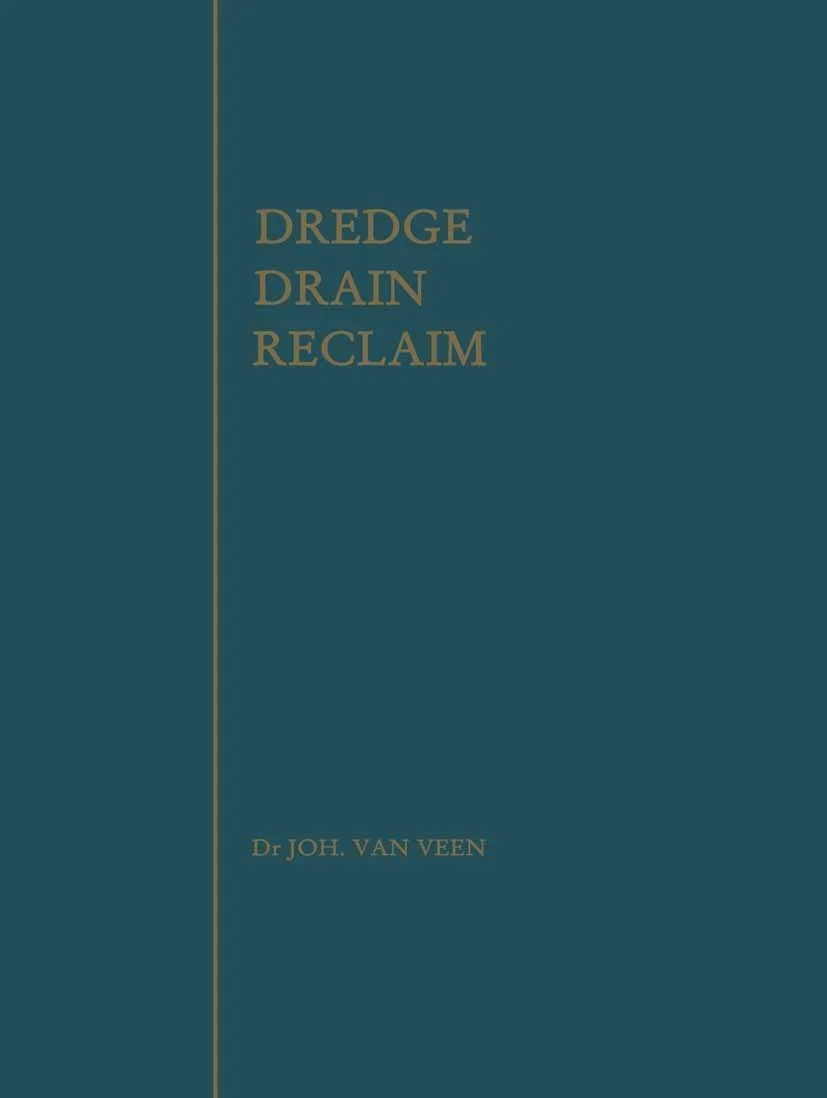

Specifically, our class investigated Dr. Johan van Veen’s Dredge Drain Reclaim: The Art of Nation, which explores Dutch water management. The first chapter traces the history of Dutch resilience and communal responsibility in managing water, from mud-piling in Friesland to dike-building expertise exported worldwide. The second emphasizes the art and impact of dredging, which helped transform Dutch cities into major ports. Chapter three delves into land reclamation, particularly the ambitious Zuiderzee project, capturing post-WWII optimism and Dutch engineering prowess. The final chapter defends the costly yet visionary Delta Works project, arguing that long-term national safety outweighs short-term economic concerns.

First published in 1948, with the book’s 5th edition published in 1962, Dredge Drain Reclaim references water issues that persist in the country today. The Netherlands faces urgent water management challenges due to rising sea levels, increasingly extreme storms and river discharges, and long-term droughts. Existing systems struggle as rivers can no longer effectively drain into the sea, while prolonged dry periods threaten freshwater supplies and natural ecosystems. In low-lying areas, subsiding land—exacerbated by artificially low water tables—makes these issues worse, leading to increased saltwater intrusion that compromises both agriculture and drinking water sources.

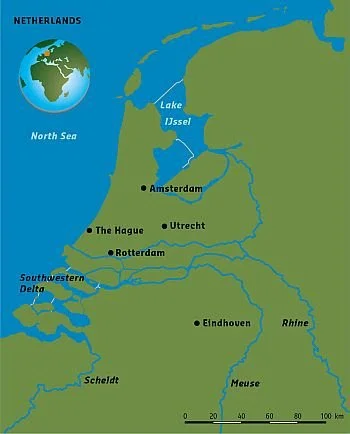

Located on the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt Delta, where three great rivers meet the North Sea, Nederland, or “low country” in Dutch, is essentially Europe’s drain, channeling rain and meltwater from half the continent. Meanwhile, tides, winds and storm-floods from the North Sea have both constructed and deconstructed the sandy coastline. After the sand dunes formed, swamps took shape, through which water from the three rivers pushed its way through—carrying sediments, clogging inlets, and winding towards the sea. The sea carved through the swamps, adding layers of marine sands and clay. In its natural state, the Netherlands is a fluctuating patchwork of sandbanks, dunes, islands, peat bogs, and clay marshes shifting with the wide rivers and estuarine inlets.