During

Our group took a red eye from Philadelphia, PA and landed in Schipol, Amsterdam. We took notice of the flat landscape and learned how the airport was built on what used to be a lake bottom, -5 meters below sea level.

Bird’s eye view of Schiphol Airport

Photo credits: WikiWand

For six nights, we made Rotterdam our home base, with day trips to other cities. But, we began with a tour of Rotterdam itself.On our first full day in Rotterdam, we met up with Yasmin, our tour guide from Architour, who is also an architect, urbanist and futurist. She brought a large booklet of hand-drawn maps to help us visualize historical land use, water management, climate adaptation, and the functioning of features we encountered on the tour. She believes drawing is the language of interdisciplinary work.

We started at the historical center of the city, which is marked by statues of feet. The artwork, entitled “Everyone is dead but us” by Ben Zegers, refers not only to the city’s origin, but also the spot’s ancient purpose as a market.

Yasmin, our tour guide from Architour, holding a hand drawn map of the Netherlands.

Statue of a foot, by Ben Zegers, at the historical center of Rotterdam. Taken on March 9th, 2025.

Rotterdam is a harbor city stretching 40 km. It used to be the world’s biggest harbor, facilitating large amounts of trade for the continent. During WWII, in 1940, the city was bombed by Germany and almost all buildings were leveled. The city council immediately started to rebuild during the war and turned the tragedy into an opportunity to create a modern city.

We visited Hofbogenpark, designed by Piet Oudolf, who helped co-create New York’s High Line. The public park is situated on the roof of the Hofbogen railway viaduct that used to transport people to The Hague 120 years ago. When the city planned to demolish the area to build high-rises, the local residents pushed back. The locals saw potential in the existing structures and took the lead in transforming it into a much-needed green space.

Sarika at the Hofbogenpark.

In the Zoho district, Yasmin showed us how the neighborhood has incorporated water management solutions into the urban landscape, including rain gardens, permeable pavements and other design features that help manage stormwater while creating inviting public spaces. We visited the Benthemplein Watersquare, where rainwater collects in basins that double as play areas when both wet and dry—an example of how climate adaptation can also enhance urban life.

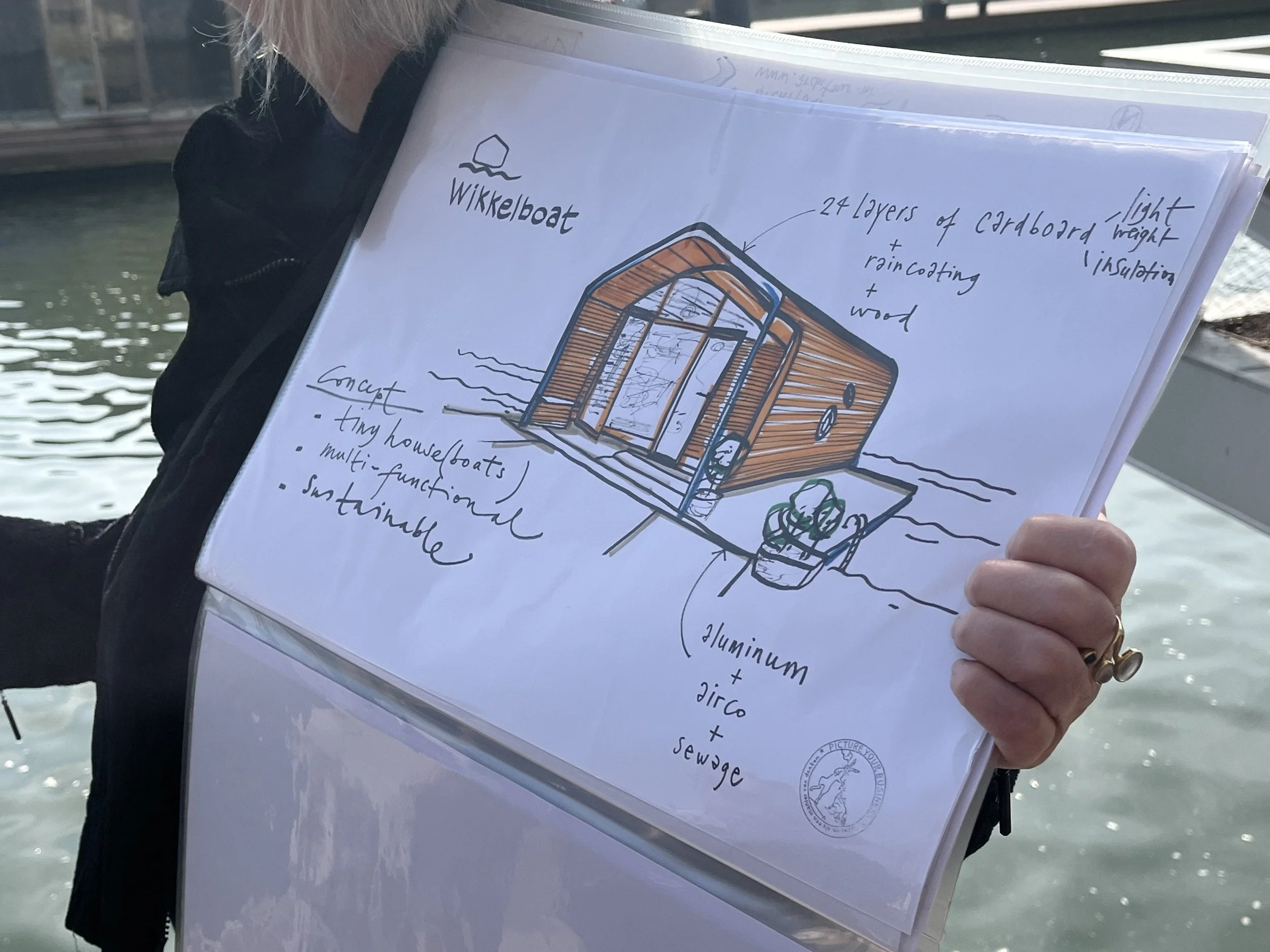

At Rijnhaven, one of Rotterdam’s oldest ports, we learned about the floating structures and plans for future innovation. In the middle of the port sits a “floating forest,” the Global Center for Climate Adaptation, as well as Wikkelboats, multi-functional, sustainable houseboats. Ambitious plans for a waterfront landscape aim to connect the diverse adjacent neighborhoods with more green space.

The Global Center for Climate Adaptation’s Floating Office in Rijnhaven.

Photo credits: Sebastian van Damme via Climate Adaptation Platform Netherlands

Yasmin’s sketch of the Wikkelboats.

“Water is the main structure of the Netherlands”

On our second to last day in Rotterdam, we visited RDM Campus—formerly the Rotterdamsche Droogdok Maatschappij shipyard.Today, the site has been reimagined as a hub for innovation, housing facilities for research, education, and entrepreneurship. The campus houses state-of-the-art labs and community space for the researchers. We learned that making the large shipyard climate-friendly had posed a significant challenge. To address heating needs, greenhouses, which inherently retain heat, were used to create separate, climate-controlled spaces for research, study, and application.

Guidepost in RDM that points to different labs.

The focus of our afternoon was “Floating Futures.” RDM students presented design solutions for floating communities as a response to embanked areas, flood risk, and the housing crisis. Some of the concepts they presented included modular floating houses, urban wetlands, greenhouse-domed botanical gardens, and fish highways.

Penn students followed with research on the social and political dimensions of floating developments—exploring how to address public concerns, investor skepticism, and policy barriers. Our work aimed to bridge the gap between design and real-world implementation.

The exchange sparked thoughtful discussion, and both groups expressed interest in continuing the conversation—laying the groundwork for future cross-continental collaboration.

Penn Students presenting on their vision for a floating future. From the left: Peace, Morgan, Allison, and Sarika.

Roos, a student from Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, presenting her vision for a floating future.

Memory SnapshotsTour of Brienenoord Island

Following presentations by Han Mayer and Anke Dielissen from ARK Rewilding, Anke guided us through the island’s tidal park. Its success is now inspiring plans for more tidal parks in the harbor.

Visiting the one-and-only Floating Farm

The Floating Farm is a self-sufficient dairy farm in Rotterdam’s old port that produces fresh milk and cheese for local consumers. The project prioritizes sustainability, including collecting rainwater and converting cow manure into heat.

Dinner with the Experts

We had the honor and privilege of dining and conversing with Peter Glas, the former Delta Commissioner, and Marjolijn Haasnoot, Professor at Utrecht University, senior researcher at Deltares, and member of the Wetenschappelijke Klimaatraad (WKR).

Against the bittersweet backdrop of our last day, we began with a bike tour of Amsterdam Noord, the borough where we were staying, just a ferry hop from Central Station—Amsterdam’s main transportation hub.Lot Locher, International Director of Climate at One Architecture & Urbanism, graciously gave us a guided tour to discuss the history, architecture, and urban planning of the Amsterdam Noord.

Lot Locher, wearing the yellow beanie, speaking to the group in front of the North Sea Canal.

Twenty years ago, Amsterdam-Noord was not considered part of Amsterdam. It was a place no tourist visited, where prisoners were hanged and the shipyard industry took hold. But Lot described how the best change in Amsterdam happened when the city made the leap to explore and develop this area.

“The best change in Amsterdam [was Amsterdam Noord]”

Biking through the area’s industrial landscape, with dry docks and storage yards, we crossed canals and cycled parallel to piles of shipyard materials and water basins where seagulls rested. A strip of graffiti-covered industrial buildings led us to a warehouse that had been converted into a graffiti museum. The city’s independent creatives carved out space here, leaving a legacy on the sides of buildings, renting out cheap studios, and creating community. However, after the redevelopment, gentrification is pushing the independent creatives out, with more established organizations taking their place.

Lot leading us down onto the polder of Tuindorp Oostzaan.

We continued our cycle through Tuindorp Oostzaan, a historic garden city situated on a subsiding polder. We passed rows of quaint houses. Constructed in the 1920s on a concrete slab, the village is experiencing significant subsidence issues. These include salt water intrusion, fresh water contamination, and structural damage such as cracking walls. With the groundwater just a foot beneath the topsoil, residents are also dealing with persistent dampness in their homes and flooded gardens. Developed to house the working class employed by nearby industries and shipyards, the neighborhood reflects the struggles of a socially vulnerable community.

In 1960, a flood disaster brought this working-class community closer than ever before. Since then, the tight-knit residents have since resisted redevelopment efforts, despite the city’s promises of sustainability benefits. Ongoing gentrification has deepened mistrust in the government. A large photograph in the village center memorializes the 1960 flood, serving as a lasting reminder of the event.

Photo memorializing the 1960 flood in Tuindorp Oostzaan.

At the town’s water square, Lot described a project she is currently working on known as Ground for Wellbeing. Water squares throughout the Netherlands serve as multifunctional spaces designed to manage excess rainwater while also providing a public area for community activities. Kids play in the excess rainwater during the summertime. Understanding the precarious social, economic and environmental situation of Tuindorp Oostzaan, the Ground for Wellbeing project’s innovative municipal planning approach aims to enhance climate resilience and improve residents’ health and wellbeing. With funding from the EU Commission and the city of Amsterdam, the team is committed to making this a social project that involves the community in the planning and development. Notably, they are using a novel organization model known as “Zoöp,” where a representative advocates for the voices and interests of non-human life. Additionally, they are conducting Urban Rhythm Analysis, adopting a temporal-social-anthropological approach to understand how people move differently on a daily and seasonal basis.

Water Square of Tuindorp Ooastzaan where the Ground for Wellbeing Project is designing a more sustainable and socially inclusive public space.

when it was time to wrap up the trip, we didn’t want to say goodbye...